An Exploration of Other Ways of Knowing & Land, rooted in Raleigh, North Carolina, ca. 1930

Dr. Anna J. Cooper ❤️🔥

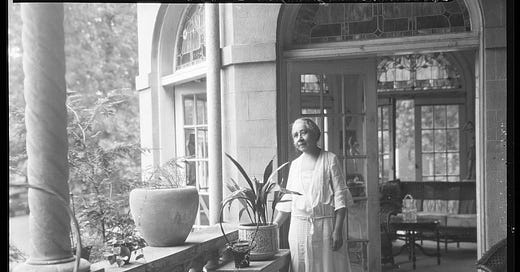

📸: “Dr. Anna J. Cooper in her garden, home & patio [No. 12, Dr. Cooper on her patio: photonegative, ca. 1930],”Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution

When I came across this image I knew it would make its way into the archive because of the subject of the photo. This photo is so important to the foundation that D.O.T.S. is built upon! The first thing I adore about this archival image is the contrast of heaviness and lightness present in the picture.

I am intrigued by the heaviness of the strong foundations for the many plants to rest on. We can see the heavy foundations in the photo in places such as the balustrade (railing of the patio). Yet, there is lightness present in the photograph that brings balance & harmony. There is sunlight coming in from the left side of the frame. This light highlights the exterior of the home/patio & the subject’s, Dr. Anna J. Cooper's, face & all-white ensemble.

I first encountered Dr. J. Cooper through the work of scholar & writer Dr. Brittney C. Cooper. Sharing the same last name is not the only thing these two Black Women scholars have in common. Both women hail from the U.S. South. Dr. C. Cooper is a proud Louisianian & Dr. J. Cooper was enslaved in a domestic home in Raleigh, North Carolina. While this photograph of Anna was taken in her home in Washington D.C., Anna was a Southern woman through & through.

Anna’s book entitled A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South was published in 1882. Within this book, Anna expressed her fundamental belief “that we cannot divorce Black women’s bodies from the theory they produce” (C. Cooper, 2017, 3)1. In other words, Anna believed in the knowledge that Black Women’s bodies produce & wrote that theory starts in the body. This is now something that many are calling “embodied knowledge.” Furthermore, Anna makes a clear distinction between respectability versus what she coined “undisputed dignity.” Brittney goes on to explain the difference between Anna’s two terms below.

“The call for dignity and the call for respectability are not the same, though they are frequently conflated. Demands for dignity are demands for a fundamental recognition of one’s inherent humanity. Demands for respectability assume that unassailable social propriety will prove one’s dignity. Dignity, unlike respectability, is not socially contingent. It is intrinsic and, therefore, not up for debate” (C. Cooper, 2017, 5).

Anna’s use of her pen to record how Black Women move through the world using the knowledge our bodies create partakes in the mirror moment of other ways of knowing. Although knowledge does not have to be recorded to be validated, Anna’s pen gave voice to what many Black Women have always known. There is a power in seeing what you have always felt (embodied) be expressed, celebrated, & show up in a myriad of other ways in the world.

Today, Dr. Anna J. Cooper is praised as one of the earliest Black feminists! According to Columbia University in the City of New York, “In 1925, at the age of 67, Cooper became the fourth African American woman to obtain a doctorate of philosophy.” While she started her doctorate program at Columbia she finished/earned her degree from the Univerisity of Paris in France. Within the context of this archival photo, ca. 1930, we see Dr. J. Cooper on her D.C. patio because “in 1930, Cooper retired from teaching to assume the presidency of Frelinghuysen University, a school for black adults.”

While this photograph is taken miles away from her Raliegh roots, the importance of land/nature/plants is evident within the frame. The sprawling plants remind me of my own grandmother’s many plant stands. Therefore, while the landscape of D.C. varies vastly from the South, Dr. J. Cooper maintained her voice & connection to nature as a Black Woman of the South in the many places she took up space in.

COOPER, BRITTNEY C. “PROLOGUE.” In Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women, 1–10. University of Illinois Press, 2017. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1q31sfr.4.